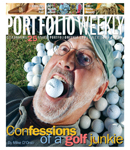

Portfolio Weekly

So this is what they meant. This is what they warned me it would come to.

A fierce, dark morning in March. Fifty-mile-an-hour winds ripping in from the northeast, shearing leaves and limbs off the pines and oaks lining the fairways. Sheets of silvery rain sweeping across the greens, soaking our clothing, stinging our skin, turning our strongest tee shots into weak, pathetic flares.

And still we played on, 118 of us, all members of the Tidewater Amateur Golf Tour, scattered across the layout of Newport News’ Kiln Creek Golf Club, slogging our way through the opening tournament of the 2008 season.

This is what my friends had predicted, the ones who were already into this game when I decided to take it up some six years ago. Until then, I was like most everyone else. Once every couple of years I’d pull my bag of yard-sale clubs from the garage, dust off the cobwebs, pick up a cold six-pack on the way to the course and spend the next five hours hacking my way around some municipal dirt patch with two or three of my buddies.

I felt about golf the way you probably do. A waste of time and money. The province of rich, fat Republicans in Sansabelt slacks and lime-green polo shirts, sucking expensive cigars and betting more money on a back-nine Nassau than most of us make in a month.

Me, I preferred real sports. Like basketball. I kept my Nike high-tops and an inflated Spalding in the trunk of my ’76 Cutlass till I was into my mid-forties, always ready for a full-court run with the brothers at some outdoor hoops in the city. I kept a bat and glove back there, too—for baseball at first, and then, as the years passed, for slow-pitch softball. Serious slow-pitch. You know what I mean, those of you who play it. We’re not talking about company picnics or the Fourth of July, goofing around with the wives and kids. This is the real deal. The only thing slow in this game is the pitch. Everything else—the hitting, the fielding, the baserunning—is fast, hard, sharp as anything you might see at Harbor Park. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, check out a top-level ASA or USSSA tournament anytime between now and Labor Day. You’ll have no trouble finding one; there are two or three taking place somewhere in Hampton Roads every weekend.

Basketball. Baseball. Tennis. Softball. These are sports. But golf? Gimme a break. Golf is not a sport. Golf is a game. Yes, it requires skill. So does darts, or horseshoes, or billiards. These are games. Athletes play sports. You don’t have to be an athlete to pitch a horseshoe or pocket a nine-ball…or stripe a 5-iron from 170 yards out. Look at John Daly. Or Craig Stadler. Or Allen Doyle. Great golfers. But athletes? Please.

These were my feelings about golf…until a sweet summer evening some six years ago, when a pair of close friends (in the interest of full disclosure, I’ll give you their names— Thom Vourlas, co-owner of the Naro Theater in Ghent, and his wife, JoAnn, a teacher at Maury High School) asked me to join them for an evening at the now-defunct Indian River driving range out on South Military Highway. Talk about a dirt patch.

But something bit me that night that I’d never felt before. I can’t explain why. Maybe it was the fact that basketball was now behind me (bad ankles). As was softball (I’d retired from slow-pitch after moving from Williamsburg to Norfolk, leaving behind the team I’d played with for more than a decade). For the first time in my life, I had no sport, nothing into which I could pour my competitive juices. What I did have—more than ever before—was time (I now worked for myself, out of my home) and money, enough to afford an actual set of clubs and the cost of a couple of lessons.

Lessons. This was a sign that I was headed over the brink. Throughout my life, all the way back to high school, I’d clung to a hardcore conviction (shaped, I’m sure, by my leftist tendencies) that a paid "lesson" in any sport was some kind of bourgeois indulgence. I was a purist. The journey to knowledge, to excellence, was meant to be a solo excursion, unguided, a process of trial and error. Wisdom, I believed, was only acquired through pain, through failure, through the school of hard knocks. This was the way of the Japanese koans I enjoyed reading. Chop wood, carry water. This was the process I believed in, that the path to truth, to the top of the mountain, was a way strewn with missteps, groping and hacking your way into, through, and, finally, out of the woods, without the help of maps or instructions. I had no idea that those metaphoric woods would one day become literal, strewn with errant Top-Flites and Titleists.

This was my attitude back in the winter of ’75, when, after graduating college, I headed west to Colorado and found myself in the then-drowsy little Rocky Mountain village of Breckenridge. (This was before the Aspen Corporation bought the place and plastered it with condos, boutiques, mini-malls and sushi bars.) I’d been on skis only once in my life, but was out for raw adventure and so there I wound up, in what was then a rough-edged enclave of hardcore ski bums, hippies and hermetic lead miners who lived in hand-built A-frames tucked back in the aspens. We worked and skied by day and gathered each night in the Gold Pan Saloon (the oldest continuously active bar west of the Mississippi—or so a plaque by the front door pronounced), where a thick haze of marijuana smoke hung over the pool tables in the back room, Willie Nelson crooned "Blue Eyes Cryin’ in the Rain" from the jukebox, and a fistfight would break out about once a week, working its way into the front barroom before the loser was finally hurled through the floor-to-ceiling front window, coming to rest on the snow-packed asphalt of the town’s only paved road. That would be Highway 9, a two-lane artery that carried you north toward the money of Vail (where Gerald Ford kept a condo), or south toward an even more remote little mining town called Fairplay, the place Trey Parker and Matt Stone would use some 20 years later as their setting for South Park.

As I said, I’d skied only once in my life before I arrived in Breckenridge, but I was damned if I was going to take a—it was hard for me to even utter the word aloud—lesson. Instead, I spent the first half of that winter sliding down the mountain on my ass before I finally learned to stand up and actually ski. It took me three months to learn what would have taken me maybe one week to master if I’d simply dropped my silly, sophomoric "purity" and taken a couple of freaking lessons.

Fast forward nearly three decades, and here I was, under the lights off Military Highway, slicing golf balls into the starlit sky…and absolutely loving it. The visceral sensation of the occasional pure shot, the compression of the ball against the sweet spot of the clubhead, the perfect parabolic flight of that gleaming white pearl as it arced into the distance—I’d never seen or felt anything quite so gorgeous. Golfers who stroke such shots routinely say it’s better than sex. I feel sorry for them. That says more about their sex lives than it does about their golf games. But I can tell you this, having played my share of other sports: There is something transcendently radiant about the feel and the sight of a perfectly-struck golf shot that eclipses the sensations of all other games.

Unfortunately, the flip side of this coin is just as extreme. There is nothing as disgustingly repulsive as a poorly-struck golf ball: a duck hook, a slice, a scalped worm-burner, or that foulest of all shots, a word most golfers are afraid to pronounce, as if it might be contagious—the shank, that most miserable of mishits, which sends the ball veering away on a sickening slant.

Needless to say, four out of five of my swings that first night at Indian River were shanks. Even after several lessons and months of practice, I never knew when a shank would rise up out of nowhere and bite me, like a hidden cobra. But with time, they became fewer and farther between. Golf, as they say, is a game of misses. You know you’re improving when your misses get better. The one advantage of having played other sports was my understanding of failure. A .300 hitter in baseball is better than average—yet he fails seven times out of 10. Novice golfers who have never played any other sport can be recognized from miles away. They’re the club-throwers, the cursers, tossing a tantrum every time another shot skips into the weeds. They don’t understand that you’ve got to be bad at something before you can be good at it; and you can expect to be spectacularly bad at golf before the learning curve begins climbing.

So many beginners just don’t get this. And golf attracts more full-grown beginners than any other game. No one decides to start playing basketball in their mid-forties. Or baseball. But golf—everyone thinks they can just go buy some clubs, take a few lessons, and conquer this game. They watch it on TV. Tiger. Lefty. Ernie. Annika. These people make it look so easy. Most middle-aged beginning golfers are men or women who have typically fashioned successful careers. They’re accustomed to facing a challenge and overcoming it by sheer will and determination. When they apply that same work ethic to this game and get such hideous results, they go ballistic. They’re not used to failure, and golf is a game rife with failure. It’s how you recover that makes all the difference in golf. Every sport likens itself in some way or another to life itself, but no game mirrors the lessons of living more so than this one—how to balance intense focus with inner calm; how to leave a bad moment behind and relish a good one; how to know your limits; how to play by feel and instinct as much as mechanics.

And, over and over, again and again, how to deal with adversity.

The image of country club elitists that I had before playing this game was erased by the time I’d spent several months playing courses like Ocean View and Lake Wright in Norfolk and The Woodlands over in Hampton. There’s an undeniable democracy at these places that is found in few other sports. I like to go out by myself and join up with a twosome or threesome on the first tee. Nobody asks what you do for a living, how much money you make, where you went to college, or if you went to college. Nobody cares. You just tee it up and play. After eight or nine holes, you might begin chatting and learn that one of the guys is a lawyer, that the dreadlocked dude is a Rastafarian chef at a local restaurant, and the guy wearing jeans, a T-shirt, and a grease-stained ballcap is an auto mechanic. He also plays to a 6 handicap.

I was out at Ocean View one afternoon a few years ago and caught up with a threesome waiting to tee off on the par-five 16th. They looked to be in their late 20s, slackers in cut-offs and sneakers. They were having a blast, knocking balls into the lake while they waited for the group ahead of us to move on.

They said they were from out of town. I asked what they were here for. They said they were a band, that they were playing that night. I asked where, figuring maybe The Taphouse or Cogan’s here in Norfolk, or perhaps Croc’s or Peabody’s out at the Beach. When they said, "Some place called the Constant Center," I almost fell into the lake.

These guys were Green Day, in the midst of a nationwide tour with the year’s number one album, American Idiot. Their gig that night was a sellout at ODU’s Ted Constant Convocation Center.

I loved it. Three gazillionaires who could play anywhere they’d like, and here they were, at scruffy Ocean View, chugging cold Buds and having a ball. We talked about rockers and golf, about Alice Cooper and the huge celebrity tournament he hosts every year.

These guys got it. They understood this game. They were terrible, but they were having a great time. They told me they play almost everywhere they go. They each store a set of clubs on their tour bus. They want to score well just as much as that lawyer does. Or that Rastafarian. Or me. They told me they hit the practice range whenever they can.

And yes, they’ve taken lessons.

I have no doubt that had they been entered in that Kiln Creek Tournament, the boys of Green Day would have stayed out in that cyclone just like the rest of us.

My friends were right about where this game would ultimately take me.

Obsession.

Addiction.

No doubt.

But far from a warning, I look at their words now as a prophecy. As a promise. We all need a place into which we can throw ourselves, lose ourselves, maybe find ourselves if we’re lucky. For some, that place is a bottle. For some, it’s a book. There are as many places to look as there are people. For me, and some 30 million other Americans (according to the National Golf Foundation), it’s a bag of irons and woods, a soft rolling fairway and a well-groomed green. For those of us who get it, like Green Day, no matter our score, we couldn’t be happier.

Come rain or shine.

Norfolk resident Mike D’Orso, a former reporter for The Virginian-Pilot, is the author of 15 books, including Eagle Blue, published last year.

His league handicap is currently a 15.