April 19, 2009

Norfolk resident builds berm to protect home from floods

By Jeanne Mooney

The Virginian-Pilot

Click images to view them in a larger gallery

Most days, the Lafayette River spits up none of the mess that got Mike D'Orso scheming about how to keep his Norfolk home high and dry. Most days, the river churns quietly past his Colonial Place neighborhood, leaving crawl spaces, ductwork and flooring alone. But rust-stained curbs along the street where D'Orso lives hint of the river's foul mood.

The place "is the floodiest of flood zones," D'Orso said. Photos of water lapping at his and his neighbors' doors leave little doubt.

D'Orso might have jacked his home higher to raise the elevation of the first floor above its original 8 feet. But a long-legged Tudor-style home would look stupid and ugly, he decided.

He wanted a wall. Better yet, a berm. Nine years ago, he trucked in 20 loads of dirt to protect his property against the nearby river. Today, he wonders if the river will win out.

"It's rising higher and more frequently every year," D'Orso said.

D'Orso may be the Lafayette River's most worthy opponent. The former Virginian-Pilot reporter has spent years following and writing about people who make their way in extreme environments.One of his 15 books follows a boy's basketball team from Fort Yukon, Alaska, in its attempt to trump systemic misery and win a state title. D'Orso published "Eagle Blue: A Team, A Tribe, and a High School Basketball Season in Arctic Alaska" in 2007.

Another book tells the sordid story of how opportunists have altered a tropical paradise where Charles Darwin once roamed. D'Orso's "Plundering Paradise: The Hand of Man in the Galapagos Islands" was published in 2003.But even before those writings, D'Orso staked a claim of permanency. He bought his Mayflower Road home in 1993 and made it the stable address he sought as a child. His father, a Navy submariner, had moved his family every few years.

"I want to stay here till I die," he said.

The home has been updated dramatically in D'Orso's 16 years as owner. Contractors added first- and second-floor decks and a 20-by-26-foot Florida room to the back of the home. They removed the stucco-like exterior finish around parts of the front and rear facade and replaced it with cedar shakes. And they enlarged the kitchen and gave it a vaulted ceiling.

Mid-2000, after the deck and sunroom had been remodeled, D'Orso got serious about protecting his home from flooding. He already had replaced ruined ductwork, he said.

"I got the idea to encircle the house with a berm."

Landscape designer Shawn Anderson said berms are an acceptable means of buffering residential communities from nearby highways. They cut noise, act as a barrier and afford some privacy.

But surrounding a home with a berm? That was a first for him. And a last, too. At least, for now.

"I've never done another job like it," said Anderson, owner of Visionscapes Land Design Inc. of Chesapeake.

Anderson began the first of two berm build-ups at D'Orso's with a horseshoe-shaped wall that curves gently around the front of the home, about 20 feet from it. And he began the wall that stands chest high on the 6'1" D'Orso with a trench.

Filled with stone, metal rods and a specialized concrete that cures in water, the footing supports the wall that brackets 20 truckloads of dirt. Anderson's crew bulldozed the fill so that it slopes gently from the sidewalk to the wall.

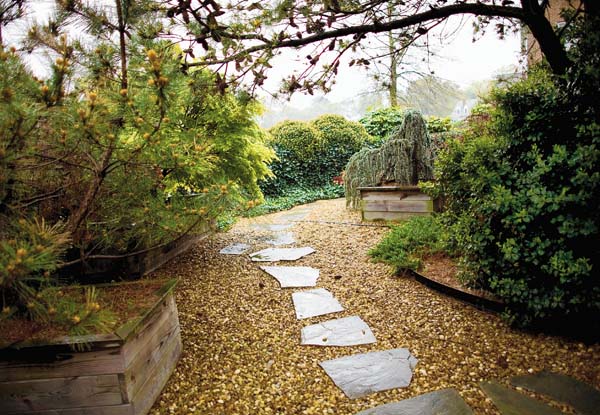

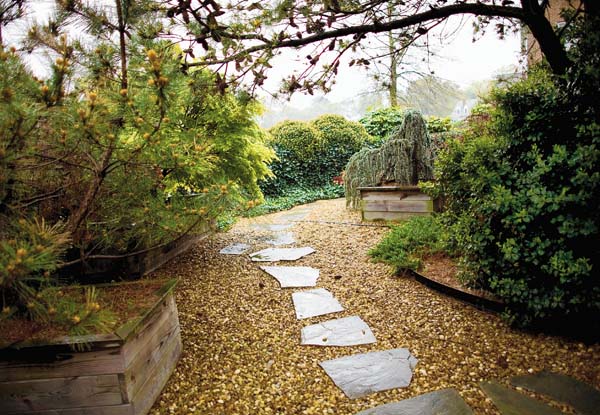

On the river side of the berm Anderson planted salvia, dwarf burning bush, dwarf fountain grass, artemesia and Indian hawthorne. Ivy spills over the leeward side of the wall onto a gravel path. Shielded from the road and river by the landscaped berm, the path feels like a private sanctuary, sunk below grade. In fact, it is at grade.

"We wanted it to feel like a garden," Anderson said.

A visitor to D'Orso's home quickly finds that inner sanctum. The front brick walkway rises to the top of the berm, drops down a few steps to the gravel path, and rises again on brick steps to meet the front door.

When Hurricane Isabel struck in 2003, D'Orso watched from a second-story window with Nippy, his cat, as the river water rose to within feet of the berm's crest.

It never capped the crest. Instead it rushed to low ground around the back of the home and berm. Some water bubbled up through D'Orso's sunroom floor.

"This was like Chinese water torture," he said.

The storm triggered phase two of the berm building. Anderson closed the loop of the horseshoe-shaped wall and trucked in 10 loads of dirt to raise the grade of the back yard to about waist height. He also dug two ponds. A path of slate and crushed stone winds past the ponds, over rocky stream beds and up to the waterfalls.

Since the berm building, D'Orso has had one maintenance issue. The pump that pushes water from the grid of perforated pipe under the stone paths to a collection basin stopped working automatically, Anderson said. A friend fixed the pump this week.

"I think it has proven itself to be very successful," Anderson said of the berm system.

D'Orso tallies his cost for the berms, walls, landscaping, walkways, water features, and sprinkler, pump and drainage systems at about $159,000.

"I'm doing this to make the place I live in be the place I want to be," he said.

Flooding remains an issue.Joel Chou, D'Orso's next-door neighbor, said the city should raise the grade of Mayflower Road by 12 to 18 inches. River water regularly caps the curbs in places when the tide is high, he said.

Chou, an architect, went to great lengths to build on his lot, which he bought in 1984. He recalled city engineer telling him it was at one foot elevation, among the lowest in the city, and created with dredged river bottom.

Chou spent an estimated $90,000 to shore up his site and prevent his future home from sinking. Engineers and crews built a unique foundation that rests on a fiberglass fabric in an 8-foot-deep cavity filled with 10 feet of sand. On top of that they poured a 4-foot-thick concrete slab. The typical home requires a slab 4 inches thick, he said.

"The house is very stable," Chou said.

Like D'Orso, Chou added topsoil to deter flooding. Crews trucked 14 loads in recently. He's been spreading it around the yard.

"It's an ongoing battle," he said.

D'Orso considers himself fortunate. He's still writing books, still living in a comfortable home and still playing out a man-versus-nature drama.

"My attitude is, if I lose everything I'll be OK," he said. "Who could complain?"

CLOSE WINDOW